The art historian Leo Steinberg once called Leonardo da Vinci’s “Last Supper” “the most thought-out picture in the history of art.”

Commissioned by Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan, in 1495 for an end wall in the refectory of the Dominican Church of Santa Maria delle Grazie in that city, the 15-by-29-foot painting depicts the dramatic moment when Christ announces to his disciples that one of them will betray him. Traditional analysis of the “Last Supper,” which was completed in 1498, has emphasized its subject matter, composition and style. But a deeper look brings out the true genius of the work: the relationship between art and architecture, the way science can bring man closer to God, and an outline of the quintessence of the divine.

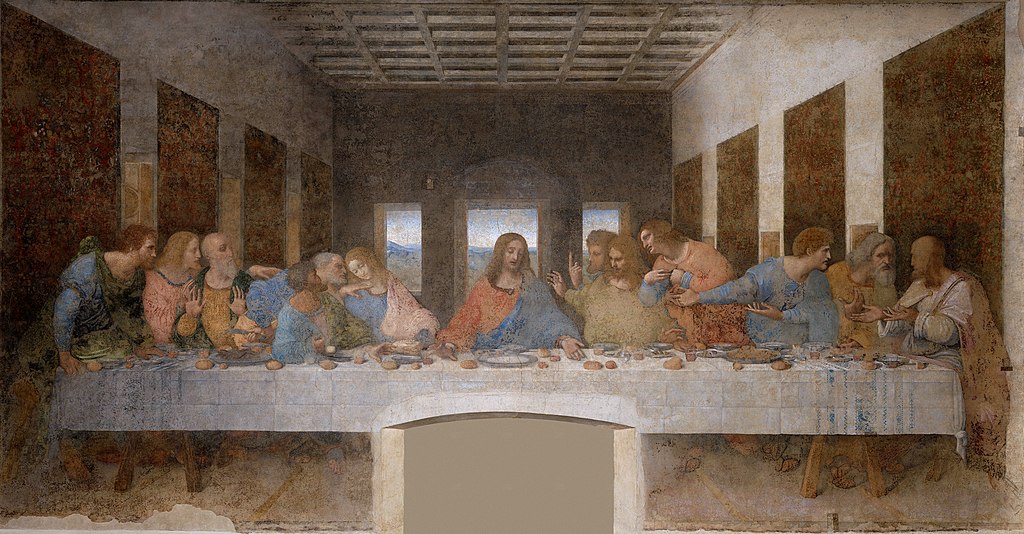

The first thing one notices is that the imagery of the Last Supper is aligned with the room’s architecture. The fictive walls of the painting are extensions of those of the refectory itself, while the illuminated right wall within the painting indicates that its primary light source is outside the picture, a window in the dining hall on the viewer’s left. The idea was to create the illusion that the monks eating in the dining hall were witnesses to this cataclysmic event. (In fact, the table Christ sits at is thought to be identical with those used in the monastery in the late 15th century.)

In religious terms, the “Last Supper” forecasts Jesus ’ destiny and validates a lineage foreseen by the prophets of the past as the events of the then-present unfold into the future. We can be certain that every person in that room understood the religious and historical ramifications of Christ’s words. So the challenge Leonardo faced was finding a way to convey its drama and monumental significance in pictorial form.

The emotional dynamism of the apostles’ reaction to Christ’s words is only one way Leonardo does this. The artist captures the anxiety and tension of the announcement by squeezing all 13 men into an uncomfortably small space. The table, as has often been noted, sometimes critically, is too small to properly seat everyone. That’s the point. It generates a feeling of unease and discomfort, like being crammed into an overcrowded elevator.

The other way derives from the second light source at the rear of the image. This is the evening before the day of the Crucifixion. The setting sun behind the mountains has many connotations with respect to the scene. First, the overt reason for the meal is to celebrate the Jewish Passover. The Seder begins at sundown, so the event is placed in the proper religious doctrinal setting.

Second, in Early Christian art Jesus had become associated with the sun, its setting and rising each day a metaphor for his death and resurrection. Its placement directly behind him in the painting highlights this association. Hence his appearance as Sol Invictus (“Unconquered Sun”) in, for example, the third-century mosaic in the Vatican grottoes under St. Peter’s Basilica. The solar equation persists in later art as a halo, a nimbus of light representing the circle of the sun. But Leonardo’s “Last Supper” differs from virtually all earlier versions in that he does not include a halo, instead using the light of the setting sun.

The sun in Leonardo’s conception is crucial to communicating the most important aspect of the entire fresco: Jesus’ impending death as a consequence of the betrayal he announces. Leonardo uses the relatively new technique of linear perspective, placing the vanishing point such that if Jesus turned to look out at us it would be between his eyes. More than a pictorial device, it reinforces the Renaissance idea that linear perspective, with its basis in mathematical reason and the principles of vision, leads one toward God.

But the true genius of using linear perspective is that its elements—a vanishing point and a horizon line—express the painting’s scriptural message. Horizons imply a sense of time. We speak of something being “on the horizon”—taking place in the proximate future. Here, it functions as the pictorial equivalent of Jesus’ words: “Verily I say unto you, that one of you will betray me.” (Emphasis added.)

The perspective that brings our vision to Christ’s head also points to the setting sun behind him. The symbol of Jesus’ identity, the sun, is falling toward the future, the next day. The two elements, vanishing point and horizon line, come together to cause the wall to literally express the final result of the betrayal, in fulfillment of the past Scriptures: “On the horizon, I will vanish.” What Christ, what the painting, what the wall are ultimately saying is “Tomorrow I will die.”

Thus past, present and future converge to create an artwork whose meaning is immediately accessible but whose spatial and semantic depth successfully merge to produce one of the greatest works of art ever created.

This article was originally published at the Wall Street Journal in 2018 here.