Comparing Kim Ki-chang to Caravaggio may seem paradoxical: the one bold and aggressive figures, the other delicate and restrained watercolors. But then, seeing painting across cultures requires empathy, intuition, and perhaps a taste for paradox.

I first encountered Korean artist Kim-Ki-chang’s Life of Jesus series while researching typical images of Jesus, like those of Leonardo da Vinci. Kim created the thirty watercolors during the Korean War as a way to cope with the personal anguish produced by his own and the Korean people’s suffering. Kim died in 2001, but his work still resonates in the contemporary art scene in the East. His paintings have been compared with current artists such as Zeng Fanzhi and others.

Kim portrays Christianity’s key moments as taking place in Korea and personified by Koreans. In The Last Supper, for example, Christ and his apostles are seated in a decidedly Asian architectural setting and the figures are dressed in traditional Korean robes and headwear.

What struck me immediately about Kim’s work is its difference amid the familiar. The Catholic artist and art-lover has this advantage: we are part of a universal Church. Watching our shared tradition inflected through another’s culture is revealing. It makes one think that Christ and his message are a form of collective memory that we all can access.

Take and eat it; this is my body. Do this in remembrance of me.

These paintings make me wonder: how might an American Catholic appreciate these images from the East? Is it possible for such Asian art to inform the spirituality of the Western mind?

To be sure, there is a long history in Western art of representing Biblical figures in scenes and wardrobes of the period in which the artist lived. Caravaggio dresses St. Matthew in early 17th-century attire. Paul Gauguin’s Yellow Christ (1889) presents the Crucifixion with the Breton women in 19th-century France. Artists who do so are underlining the immediate relevance of Christianity in their time and place. Many other non-European cultures tell the story of Christ clothed in their own people’s faces, such as the dark-skinned Virgin of Ethiopian art.

However, something different and more specific is happening in Kim Ki-chang’s collection. One senses that the use of color in the Life of Jesus is secondary in many ways. Overall, there is a monochromatic patina to Kim’s paintings that emanates an aesthetic sparseness, allowing one to grasp the feeling the paintings convey without theatrical distractions.

Color usually emphasizes emotion. Yet, the somewhat limited palette of the series augments the solemnity of the Jesus narrative, as if the artist found common cause with Christ’s suffering and consolation in his ultimate victory over it.

And they spat on Him and took the staff and struck Him on the head repeatedly.

The story of the Catholic Church in Korea is the story of the victory of hope over immense, repeated suffering.

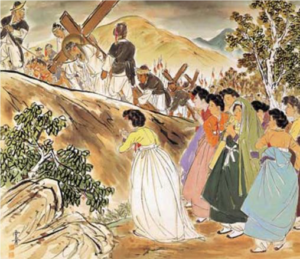

The Korean civil war inflicted untold hardships and suffering on the Korean people. For Kim, Jesus’s story resonated with what his country was experiencing. Jesus Carries His Cross in many ways captures this idea most succinctly. Christ’s cross dominates the upper register of the painting. Its significance is accentuated by the other crosses within the scene, the shapes of which are mimicked by the strong diagonal that amplifies the drama and movement of the biblical episode. Kim emphasizes its weight as it presses down against the bent body of Jesus, heightening our understanding of his burden.

…and they crucified Him.

For Christians, the cross is a symbol of Christ’s suffering. As a sign of hope, it offers reassurance that one’s grief or anguish does not take place in vain. The cross attests to the ability to endure hardship and the reward and justice in doing so. It is a message that must have resounded profoundly to the artist and the Korean people at the time.

The history of Catholicism in Korea, marred by severe persecutions, also has the unique distinction, as Pope John Paul II pointed out as he canonized 103 Korean Martyrs in Seoul in 1984: “The Korean Church…was founded entirely by lay people. This fledgling Church, so young and yet so strong in faith, withstood wave after wave of fierce persecution. Thus, in less than a century, it could boast of 10,000 martyrs.”

In the early 17th century the Jesuits smuggled books into Korea. But a hundred years later when two priests from China finally made it into Korea, they discovered 4,000 Catholics led by a small number of nobles (the only class that knew how to read). The Confucian aristocracy in Korea was appalled by Korean Christians’ unwillingness to show piety to their ancestors in the approved way. Like the early Christians in Rome, Korean Catholics refused to burn even one pinch of incense to save their lives.

By 1866, when religious liberty was finally proclaimed in Korea, there were just 20,000 Catholics in Korea. Ten thousand Korean Catholics had been martyred for their faith.

Korean Catholics were born in and of a willingness to suffer for faith. But the barbaric anguish wreaked on ordinary Koreans during the Korean War, after the humiliations and terror inflicted by Japanese rule, struck deeply into Kim’s soul. His paintings’ solemn hues reflect his own and his people’s suffering.

EMPATHY

Is it conceivable for such a deeply rooted art from an Asian culture to inform the spirituality of the American or European viewer? Quite possibly. The artistic decisions that Kim makes in the Life of Jesus series speak to the bi-directional influences of East and West inherent in his creation: Korean paintings by a Korean artist who finds spiritual solace in a religion with a prominent European aesthetic history.

Kim Ki-chang was deaf and partially mute for most of his life. He knew suffering. As a result, as an artist he was interested in understanding the story of Jesus with respect to the lives of ordinary Koreans.

The simplicity of the everyday scenes he portrays coalesces with the simplicity of rural life for common Koreans. Most Koreans lived in villages in the 1950s. The Birth of Jesus and The Adoration of the Magi capture particularly well the relationship between the pastoral lives of everyday Koreans and the humble beginnings of the Biblical Son of man.

To read the rest of this article, you can find it published with The Benedictine Institute here.