Last year, the Vatican Museums planned—and later postponed—a collaboration with the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh exploring the spiritual aspects of Andy Warhol.

To which many responded: The spiritual aspects of Andy Warhol?

Many today are still shocked to discover that Andy Warhol was, as Art Newspaper dubbed him in 2018, a “lifelong, closeted Catholic,” as the artist was primarily associated with secular culture and the less virtuous elements of modern society.

It was art historian Sir John Richardson, in his eulogy to Andy Warhol at the 1987 memorial at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, who first let the painter’s bright secret out of the bag: One of the most famous bohemian artists of the twentieth century was a practicing Eastern-rite Catholic, and who attended Mass several times a week at the traditional St. Vincent Ferrer parish on Manhattan’s fashionable Upper East Side.

Richardson, who died only this March at the age of 95, told the assembled Manhattan glitterati: “To my certain knowledge, he was responsible for at least one conversion. He took considerable pride in financing a nephew’s studies for the priesthood. And as you have doubtless read on your Mass cards, he regularly helped out at a shelter serving meals to the homeless and the hungry. Trust Andy to have kept these activities very, very dark.”

Richardson went on. “The knowledge of this secret piety inevitably changes our perception of an artist who fooled the world into believing his only obsessions were money, fame, glamour, and that he was cool to the point of callousness. Never take Andy at face value. The callous observer was in fact a recording angel … uncorrupted, no matter what activities he chose to film, tape or scrutinize.”

Richardson’s eulogy let loose a surprised flood of scholarly reflections on the relationship between Andy Warhol’s faith and his art.

Should it have been so surprising?

It was Andy Warhol, who through Pop Art transformed the wedded cults of celebrity and consumerism into icons for our national and international contemplation.

James Romaine, president of the Association of Christianity in the History of Art, in 2015 summed Warhol’s entire oeuvre: “If I had to describe Andy Warhol’s work in just one or two sentences, I would describe it as the world seen not as it is, but the world seen as it might be transformed by grace.” This fall in Pittsburgh, The Warhol Museum describes its upcoming exhibition, Andy Warhol: Revelation, as “the first exhibition to comprehensively examine the Pop artist’s complex Catholic faith in relation to his artistic production.” An exhibit of Warhol’s Last Supper in the Braccio di Carlo Magno in St. Peter’s Square would have been the capstone of this move to re-examine Warhol’s oeuvre in the light of his faith.

What would such a Warhol exhibit accomplish?

For me, it’s an exciting possibility. I teach the history of art (including the philosophy of art and other things) at the American Culture and Ideas Initiative at the Fred Fox School of Music at the University of Arizona.

The standard history of art segregates artists by time period into distinct periods and styles. Under this typical conceptual scheme, Warhol and the Vatican’s collection almost never cross paths. But a Vatican exhibition placing Warhol’s Last Supper and Skulls paintings in St. Peter’s Square breaks through the traditional dividers created by the academy to reveal something deep and important about the whole dynamic history of art.

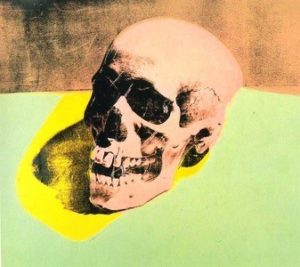

The skull as Memento Mori and the Last Supper as a representation of the institution of the Eucharist: Each has a deep history in both the Church and Art. Contemplating them through Warhol’s lens reveals something profoundly important: the close association between art, religion and humanity’s success as a civilizing force in the world.

The theory behind the American Culture and Ideas Initiative in which I participate is that the arts are embedded in the very survival of humanity. The success of the humankind has been intimately tied to our innovations and achievements in the arts. Beauty is not mere decoration or the state of being attractive, but a pathway to meaning, the search for which is after all the core, distinctively human endeavor.

In our righteous celebration of science and technology, Western culture has lost sight of these other deep roots of our humanity. The history of art is overwhelmingly religious in nature. It is the visual record of the human spirit.

This simple, obvious fact surprises many students of mine in art history courses, who register thinking that they will learn sterile facts about Picasso, Rembrandt, and Greek statues as they fulfill their arts and humanities requirements. Yet, what quickly emerges for young minds is how closely the arts are tied to both the formation of knowledge and culture, and the development of civilization.

The fundamental dynamic at play in the development of art has been our desire to understand and therefore know something about ourselves and the world through experiencing it. Art—as a heightened and rarified instance of cognitive and spiritual experience—has been pervasive within human society for this very reason. Truth cannot merely be said. It must be incarnated to be experienced in fullness by human beings.

The visual and musical arts thus mediate our lonely and separate being with the forces of Creation. Societies around the world have harnessed the order and beauty of cosmos as a way to achieve order and beauty in an earthly setting. Art allows us not to just talk about meaning, but to make it tangible.

That is one of the reasons people who have lost faith in God gravitate to the arts, looking for a near substitute. But for the great majority of human beings, again and again, across time and space and history, the order of creation and creativity was built upon a foundation of religion.

The Parthenon, for instance, is explicitly a tribute to the way in which the forces of chaos were defeated by the cosmic order and justice embodied by the gods. The balance and proportion of Greek statues of the classical period are a representation of how humans are animated with the rhythm and symmetry of the cosmos (Gk. kosmos: order). The Parthenon is often admired as a secular achievement—as an embodiment of rationality and/or democratic life of ancient Athens. But the Parthenon is first and foremost a temple created to host a devotional object: Athena Parthenos, the virgin goddess of war and wisdom.

Yes, power abused can crush the human spirit. But the primordial and chronic enemy of the human spirit is chaos. Amidst the flood of data points, of sensory inputs, and of emotions, the first task of every infant human brain is to organize, to figure out what to pay attention to and what to ignore, to recognize patterns, to discover the order which humans need to survive. Art fascinates because it commands us to master this foundational art of paying attention.

Today, art is most often encountered digitally, or in a gallery or museum. But in the great artistic flourishing of Renaissance and Baroque eras in Europe, art was mostly commissioned by and seen in the Catholic Church. Church leaders then knew in their bones that, as Pope Benedict XVI reminds us: “The only really effective apologia for Christianity comes down to two arguments, namely the saints the Church has produced and the art which has grown in her womb.”

So, before antiseptic art history courses and national museums, the arts confronted audiences with urgent and necessary meanings: spiritual didacticism, political moralism, and religious efficaciousness.

The Catholic Church was the driving force for society’s forward movement. It utilized the arts’ experiential and inspirational effectiveness to underwrite both its temporal power and its ability to convey the eternal destiny of one’s immortal soul.

This became particularly important during the Counter-Reformation, where the Church commissioned art “intended to delight, teach, and inspire” Catholics and the world, as art historian Elizabeth Lev writes in How Catholic Art Saved the Faith. The result was a recrudescence of amazing beauty: the paintings of Caravaggio, the sculpture of Bernini, and the sacred music of Thomas Tallis and William Byrd.

But this experience of the close relationship between art, faith, and human civilization is found again and again in diverse times and places: The Pharaohs used the arts to reinforce their status as the intercessor between the gods and Man. In the third century BC, Emperor Ashoka the Great of India’s Maurya Dynasty (circa 268 to 232 BC) built commemorative pillars of exquisite craftsmanship to the Buddha as a way to fortify his reign and to provide inspiration to his people. Chinese emperors ruled as Sons of Heaven, a celestial mandate embodying the later cognate notion of the Divine Right of Kings of Judeo-Christian thought.

In all these epochs, the arts mediated the way ordinary people have come to know the divine order and to find common cause with it.

In Christian culture, Man is made in the image of God. We come to see who we are meant to be through our conception of who God is: God the Creator. God the Law-giver. God the Lover. Beauty and Order were ethical ideals. Aesthetic reason was a conduit for canonical insight.

In pagan polytheism, as in the Greek myths, the gods were made in the image of Man, since they were considered ineffable in their pure unadulterated essence (consider the Jupiter and Semele myth in this regard). One way to make this relationship knowable was through the experience of beauty (think of the Bust of Nefertiti or the Apollo Belvedere) that the arts could engender.

Even when art is not explicitly religious, as when the rich and powerful (whether Dutch merchants or English nobility) commissioned secular masterpieces to celebrate their success and formalize their elevated role in civil society, art fulfilled these purposes specifically because of the visual language created by its religious heritage.

Portraits, still lifes, landscapes, and history paintings often used formal similarities to well-known religious paintings to elevate their own status, as in Madonna and Child conflations. Similarly, later modernist and avant-garde artists used the prestige and elevation of art, garnered from millennia of religious patronage to legitimate their social criticisms while simultaneously undermining traditional modes of artistic production and validation.

On the right: Elisabeth Louise Vigée-LeBrun, The Countess von Schönfeld with Her Daughter, Oil on canvas, 1793

During the late-19th and early 20th centuries, artists increasingly explored spirituality as a counterpoise to the dramatic materialism of industrialized society. Paul Gauguin, Max Beckmann, Emil Nolde, Odilon Redon, and many others employed religious figures and themes explicitly in their art as a way to tap into the expressionist core of the human soul.

Much abstract art was born of this impulse. Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, and Kazimir Malevich and many other artists used the language of abstraction to reject the materialist superstitions of the industrial world. Subjectivism as a style became a portal to spiritual reality. For if a painting does not point to a discernable external object, then all that one has left to refer to is the subjective, an internal yearning and sensory experience that was elicited through pure color and significant form.

Critics who suspect Warhol’s rendition of Leonardo’s Last Supper is disrespectful are missing the point. Warhol’s Last Supper was born out of the artists’ deep faith and points to the relevance of the Christian worldview amid the materialist culture of our time. Warhol’s Last Supper is an homage.

The Last Supper was Andy Warhol’s very last art exhibition, displayed in a former convent in Milan across the museum where the original is on display.

The French art critic Pierre Restany reported at the opening that Warhol “seemed penetrated by the importance of the moment. He greatly surprised me when he said to me: ‘Pierre, do you think the Italians will see the respect I have for Leonardo?’” Restany went on, “Consciously or not, Warhol seemed to me to having acted there as a curator of a masterpiece of Christian culture, of maintaining a tradition he was a part of.”

In a 2017 interview in Rolling Stone, Warhol memoirist Natasha Fraser-Cavassoni, who is herself British Catholic literary royalty (Her mother is Lady Antonia Fraser, the historian and novelist; her stepfather was Harold Pinter, the Nobel Prize-winning playwright), pointed out: “Almost everyone who remained relevant in Andy’s life was Catholic … Being brought up Catholic gives a sense of hierarchical order, discipline and faith. Faith, when embraced, anchors the creative” She continued, “I think it would also be fair to say that the romantically rich and multi-layered religion that forgives all – lest we forget! – allows unconventional traditionalists.”

For Warhol as for every artist deeply imbued with the Catholic imagination, Christ’s message lies underneath everyday life as its very foundation. Warhol’s somewhat unruly compositions are placed in a setting where Christ’s triangular form is displayed as the ordered center of earthly chaos. The material goods of this world find their meaningfulness in the archetype of ingesting the bread and wine—the Body and Blood—of Jesus Christ.

Daily life is an overlay built on this ancient deep truth. If one recognizes this reality, then each informs the other: the profane becomes infused with the possibility of the sacred.

The Memento Mori message, “remember death,” is a reminder of a larger order than the passing senses as well: the transient preoccupations of earthly life take second place to the eternal, divine certitudes. “Eat drink and be merry, for tomorrow we die” is bad psychology as well as morality. Keeping our mortality in mind does not mean living life with reckless abandon, but comporting oneself in accord with the Divine, with the wisdom and spirit that for Catholics is seen as a special Dispensation.

It is this juxtaposition that makes a collaboration between the Vatican Museums and the Warhol Museum so worthwhile, relevant, and crucial. Let us hope that it takes place.

Dr. Robert Edward Gordon is an Assistant Professor in the College of Fine Arts at the University of Arizona. Trained as a philosopher and an art historian, he teaches and writes about Catholic and Asian art, art and economics, freedom and its relationship to the fine arts, and humanistic geography. This article originally appeared on the Benedict Institute here.

Source Materials

- Benjamin Bennett-Carpenter, “The Divine Simulacrum Of Andy Warhol: Baudrillard’s Light On The Pope Of Pop’s ‘Religious Art’” Journal for Cultural and Religious Theory 1(3) (2001).

- Cyrus M. Copeland ed., Farewell, Godspeed: The Greatest Eulogies of Our Time (2003).

- Jane Daggett Dillenberger, The Religious Art of Andy Warhol (1998).

- Paul Giles, American Catholic Arts and Fictions (2008).

- Raymond M. Hebernick, Andy Warhol’s Religious and Ethnic Roots: The Carpatho-Rusyn Influence on His Art (1997).

- Peter Kattenberg, Andy Warhol, Priest: The Last Supper Comes in Small, Medium, and Large (2001).

- Elizabeth Lev, How Catholic Art Saved the Faith (2018).

- Ben Luke, “Andy Warhol Goes to Church” Art Newspaper (January 26, 2018).

- Robert Pincus-Witten, “Pre-entry: Margins of Error; Saint Andy’s Devotions” Arts Magazine 63(10):56 (Summer 1989).

- Nick Ripatrazone, “‘After Andy’: Getting Warhol’s Religion” Rolling Stone (August 2, 2017).

- Wessel Stoker, Where Heaven and Earth Meet: The Spiritual in the Art of Kandinsky, Rothko, Warhol, and Kiefer (2012).

- Mark C. Taylor, Disfiguring: Art, Architecture, Religion (1992).